Dating Site Scams Military

The U.S. has the most robust and powerful military in the world, and though its fighting men and women can win wars, they often appear defenseless against popular online scams.

If your service member suspects a romance scam, advise them to cut off contact right away. They should also notify the dating site. Emergency/Grandparent Scams. Being in the military carries certain risks. The emergency or grandparent scam takes advantage of a family’s concern for their service member’s well-being.

“[In] the military you have a young population on the web. They get caught up on these Internet scams, specifically targeted to them,” said Holly Petraeus, director of the Better Business Bureau’s military line and the wife of Gen. David Petraeus, commander of U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan.

Service members are targeted by websites that claim to offer special military discounts on everything from cars to apartments for rent. But the low-priced car never arrives and the easy-to-find apartment they've rented is already occupied.

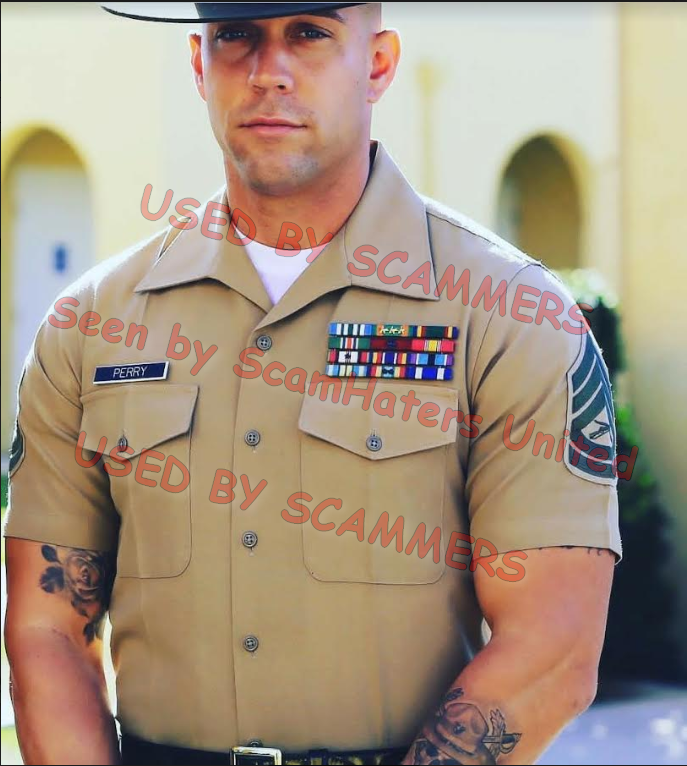

It was created specifically to warn people and spread information about these scams. The page is Military Romance Scams and has over forty-four thousand likes. There are even entire task forces arranged by the US government to crack down on these crimes. How does it work? These scams are fairly straightforward. Syria Military Scams Targeting Victims on Social Media and Dating Sites. Every day, thousands of people worldwide report being a victim to an online dating scam perpetrated by someone who pretended to be a member of the military. In recent years, Syria has become one of the hottest places for online criminals to conduct romance scams, charity. Victims may encounter these romance scammers on a legitimate dating website or social media platform, but they are not U.S.

Similarly, scammers are profiting off of U.S. civilians under the same guise of patriotism, Christopher Grey, spokesman for the U.S. Army criminal investigators, said. In the past year there has been a surge of criminals posing as military members on online dating sites, forming relationships with women and ultimately asking for money.

Scammers prey on the victims’ “kindness, patriotism and (sometimes) romance,” which compromises the good name of the military, Grey explained.

“It’s especially despicable it’s directed at our service members at a time they’ve been risking their lives for us overseas for several years,” Petraeus said. “To have somebody pick their pocket here at home is completely unacceptable.”

Unacceptable ... but often un-prosecutable.

“The majority of these scam artists come from African countries ... from Ghana, Nigeria,” Grey explained. They set up a scam, work in a cyber café, and then move.”

“They can take their website down and open up another one the next day.” Petraeus said.

When the U.S Army Criminal Investigators Office becomes aware of an online military scam, they have to hand the case over to the country where the crime is committed, Grey said.

“It’s very difficult to track these people down so we feel prevention is the cure.”

Following are some of the most common military Internet scams, according to Grey and Petraeus:

Online Dating Scams: These are the latest and most popular to hit the web. Scammers, usually out of Ghana or Nigeria steal identities of real soldiers on social networking sites like Facebook and MySpace and pose as military members. Others create identities off of British military members. After posting pictures and stories to popular dating sites, the scammers contact women. “They [build] up a huge story about who they are, they are heroes and serving the country,” Grey said. “People fall for the ploy, and some people are sending them money.” Scammers ask for everything from laptop computers to money for airfare so they can fly back to the U.S. and visit the victims, most of whom are women. “They are very poetic, they are very savvy,” Grey said. “Luring these women in and they take them for their money.” Victims have been cheated out of up to $23,000. Grey cited one case where a woman took out a second mortgage on her home to finance her romantic interest overseas.

Protest Scams: Not every online military scam is created for financial gain. Some scammers are contacting the families of military members by phone or email and making false claims that their son or daughter is injured or wounded overseas. Grey says they sometimes ask for money for medical bills, but usually they are only contacting the family to scare them as an anti-war protest.

Craigslist Car Scam: Scammers are taking to Craigslist, offering too-good-to-be-true discounts on cars for military personnel. In some cases, the scammers claim they are military members about to be deployed and need to sell a vehicle fast. Similarly, others offer military members a special discount for serving their country. More disturbingly, the scammers are offering low-priced vehicles because a U.S. military member who died in combat owned the vehicle and the family wants to get rid of it fast. The Better Business Bureau (BBB) says scams like these usually require a wire transfer and promise free shipping. The description of the cars is lifted from auto sites, and typically you can Google the vehicle ID number, to determine whether it’s a real deal or a hoax.

Military Loan Scams: Military members who have less than perfect credit are becoming victims of flashy offers that typically promise 'up to 40% of your monthly take home pay,' 'same day cash,' 'no credit check,' 'all ranks approved.' But these offers often up with sky-high interest rates that do more harm than good for military members. The BBB says that this scam involves the entire family of military members, so it can do years of damage to their financial security.

Terrorist Capture Scam: Some scammers claim to be military members fighting in Iraq or Afghanistan and who are faced with a tough decision -- they have either gained access to Saddam Hussein’s secret fortune or have captured Usama bin Laden, and need your help. This scam preys on U.S. civilians who are looking to fight justice and maybe earn a little money in the process. Scammers say they have come across millions of dollars of Hussein’s secret fortune but need a monetary advance in order to gain access to the money, and will give you a dividend when the cash is obtained. The BBB says that even though Saddam is dead, people are apt to believe that his wealth is still circulating somewhere out there. Other scammers claim they have captured bid Laden but need money to transport him, so that they can turn him over to authorities.

Housing Scams: Due to the nature of military service, those who serve and their families are forced to move from base to base around the country. Though the military often provides housing, some members are responsible for finding their own living arrangements, which scammers are fully aware of. Scammers go to Craigslist to target areas where they know military members will need housing. They lift the descriptions of legitimate rental properties and rewrite the post so it offers a special discount for military members. Depicting a too-good-to-be-true offer, they ask for a security deposit to be wired in advance to ensure their occupancy. But often, the individual or family arrives at the rental property only to find it already occupied.

The BBB outlines several tips to protect yourself from becoming a victim of military scams:

-- Always research a company with the BBB before you hand over any money or personal information.

-- Be sure keep your computer protected by installing updated anti-virus software.

-- Observe the golden rule of avoiding scams: if a deal sounds too good to be true, it probably is.

If you have found yourself a victim of a scam, you can file a complaint with the Better Business Bureau, the Federal Trade Commission or the FBI at www.ic3.gov.

In the summer of 2015, Bryan Denny received a peculiar message in his LinkedIn inbox.

“I really need to speak with you, Bryan,” a woman wrote. “I thought you were coming to visit me after your deployment in Syria was completed?”

He didn’t recognize the woman’s name or picture, had never been to Syria, and had no plans to travel to Canada, where she lived. Recently retired after serving more than two and a half decades in the Army, including deploying as part of Desert Storm, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Operation Enduring Freedom, Denny had expected to encounter some uncomfortable situations in his transition to civilian life. This wasn’t one of them.

At first, Denny just assumed she’d contacted the wrong guy — a simple case of mistaken identity. But as they exchanged messages, he came to a more troubling realization: for several months, the woman had been in a full-fledged online relationship with a Col. Bryan Denny who, it just so happened, looked just like him.

Army/Spc. Ryan Elliott

Lt. Col. Bryan Denny, then commander of the 2nd Stryker Cavalry Regiment, in a meeting with key leaders in Iraq's Diyala Province on June 15, 2008.

Whoever she’d been speaking with had gotten hold of his pictures, created a fake profile on a Canadian dating site, and constructed an elaborate, tragedy-filled backstory. The Bryan she knew wasn’t married or retired — he was a dashing American soldier whose wife had passed away and whose son had recently suffered a string of severe medical ailments. Over the course of their fleeting online love affair, she’d helped him out with hospital costs, home repairs, and plane tickets home — at a cost of several thousand dollars. Now, she was wondering where the hell he (and her money) had gone.

Denny decided to look himself up on Facebook,since that’s where the woman said she’d verified his identity. Nearly 100 accounts with his name and face popped up, each of them displaying his neatly-coiffed gray hair and steady smile. Many included shots of him with his son, while others used images of Denny with his comrades overseas. The majority showed him in uniform during his final months of service.

A lump formed in his throat as he took in one doppelganger after another. “It’s hard to capture how confusing and disturbing it is to scroll through an endless stream of profiles bearing your face and name,” he reflected in an interview with Task & Purpose. “The first time you see it, you’re just blown away.”

It turned out Denny’s name, his image, and, most important, aspects of his military service had been posted to myriad dating sites and social media platforms, all in an effort to swindle wide-eyed romance-seekers around the world out of hundreds of thousands of dollars. Maybe millions.

Courtesy Bryan Denny

Bryan Denny's military photos are ubiquitous on scam social accounts. Fighting back has proven hard, even for the combat veteran.

Although many of the fake accounts used his real name, others took on aliases to better cover their tracks, making it all but impossible to hunt them down. Every passing day brought new calls and messages from desperate women who’d been stripped of their pride as well as their life savings by “Bryan Denny.” Some women became so infatuated with him that they simply couldn’t cope with the fact that their love had been a sham — hounding him for attention until he eventually had to ignore them entirely. With his reputation and, increasingly, his sanity on the line, Denny knew he had to take action. But he was a man used to battling insurgents in firefights, not nameless, distant hackers.

Anatomy of a romance scam

In the fall of 2012, Notre Dame’s All-American linebacker, Manti Te’o, made waves across the country for his unbreaking resolve in the face of adversity. A gifted athlete and the captain of the top defense in college football, Te’o heroically carried his team to an undefeated regular season and the BCS National Championship game after losing his girlfriend, whom he’d dated online for nearly a year, to leukemia. But nine days after Notre Dame’s loss in the title game in early 2013, news broke that Te’o’s girlfriend wasn’t dead. In fact, Deadspin reported, she wasn’t real; she was a fictional online persona created by a man named Ronaiah Tuiasosopo. Te’o maintained he didn’t know the full truth of the twisted ruse until as late as December, but either way, it gained him national prestige and made him the posterboy of college football for one magical season.

Most romance-scam victims aren’t so lucky. According to the FBI, these unfortunates — often divorced, widowed, or disabled women over 40 — are being extorted by distant scammers for money and gifts to the tune of some $250 million a year. (Apple products are especially popular.)

Air Force Illustration/Lori Bultman

From an Air Force Public Affairs PSA: “A catfish is a person who pretends to be someone they're not, using social media to create a false identity with the intent of scamming someone, or worse.”

The perpetrators often operate within intricate networks; many originate in Nigeria or Ghana, where outreach tactics, compelling backstories, and conversation strategies have been turned into a science. By sticking to a formula and passionately professing their desire for a new life with their targeted victims, the scammers disarm and beguile their prey with razor-sharp precision. Just as important, these illicit organizations have stockpiled pictures and personas to bolster the credibility of their fake accounts and reel in victims with ease.

One of these scammers’ most successful ploys involves assuming the identities of lovesick American soldiers stationed abroad. It’s easy to see why servicemen have become a particularly fruitful disguise for romance scams: sterling reputations, trustworthy characters, and a built-in excuse for being away.

And yet, military romance scams are vastly underreported. Many victims are typically too embarrassed to admit they sent thousands of dollars — sometimes tens of thousands — to people they’ve never met. Denny was astonished when he finally put the pieces together and realized what was happening. Opportunistic thieves, located oceans away, saw his service, patriotism and chiseled looks… and saw a perfect piece of man candy to dangle in front of eager female suitors. Denny suddenly saw how the deference, perks, and unadulterated praise soldiers receive in America could be exploited in terrible ways when love is on the table.

A brief history of military imposter scams

In 1906, a German named Wilhelm Voigt, fresh out of prison after serving a lengthy sentence for theft and forgery, stepped into a military surplus store to initiate his greatest scheme yet. Emerging from the shop sporting a captain’s uniform, he quickly convinced a group of soldiers to follow him to the nearby town of Köpenick, where under his command, they stormed the mayor’s office and helped him loot 4,000 marks. It was only after the soldiers delivered the bewildered mayor, whom they’d been ordered to arrest, to the Berlin police that everyone realized Voigt and the money had gone missing. Though he was eventually apprehended, he became a folk hero, praised for highlighting the blind obedience of his countrymen to authority.

Military imposters have been prolific on our side of the pond, too. As the 100th anniversary of the Civil War approached in the late 1950s, Americans were captivated by a man named Walter Williams, who claimed to be 116 years old and the last living veteran of the conflict. After some digging, researchers later concluded he’d actually been a child when the war’s first shots were fired at Fort Sumter. Williams was hardly alone in this act: lying about Civil War service was then a favored tactic of fraudsters looking for prestige and pensions.

Compared to these examples, military romance scams have a distinctly disturbing — and, in many cases, sensual — flavor. Unlike your more run-of-the-mill instances of stolen valor, these schemes involve assuming the identities of specific soldiers to make victims swoon. Instead of constructing entire backstories, scammers typically tailor their characters around their servicemen’s traits, sprinkling in little pieces of truth they’ve gleaned about the men they’re pretending to be.

Denny’s imposters, for instance, frequently talked about being from North Carolina and visiting his family farm there (both of which are true), sending their targets pictures of him out in the field alongside beautiful horses. It worked: turns out plenty of women were drawn to the idea of a wholesome, sturdy country boy with a love of the outdoors and a sensitive side. As the months passed, he began receiving phone calls from women who, desperate to track him down, had taken to searching for him in his home state. In a few cases, they even got hold of his parents. “I’m actually pretty lucky that I’ve only got a cell phone,” he said. “My folks get it a lot worse, since they’ve got a landline that’s publicly listed and easier to find.”

By late 2015, Denny was receiving a weekly barrage of calls and messages from frenzied women. His wife and teenage son were getting contacted. Some of the victims had become so entranced that even after being told they had been duped, they couldn’t let go. “I’ve had to end up blocking a few of them because they just can’t sort out what’s real and what’s not,” he said. “It consumes them. There’s one particular woman in Germany who, I’m sure, has pictures of me on her fridge and thinks I’m going to visit her someday. It’s not funny. It’s quite sad.”

As a result of such interactions, Denny has become an expert at letting lonelyhearts down easy, writing hundreds of reverse “Dear John” letters to those who’ve fallen for him. He’s also had to learn how to pinpoint and eradicate fake accounts using his information. Since his now years-long search began in December of 2015, he’s identified roughly 4,000 bogus Facebook profiles that utilize a mixture of 51 different photos of him. Last fall, he got a meeting with Facebook executives to talk about the problem, but they weren’t particularly helpful. “At one point, the senior leader we spoke with just laughed out loud at us,” he said. “It was really trite, really condescending, and wreaked of an unprofessional disdain for responsibility and big picture solutions.”

Facebook declined to comment on its meetings with Denny for this story, but a representative for the company told Task & Purpose in April that the social network is doing everything it can to ensure the safety of its users. “Staying ahead of those who try to misuse our service is a constant effort, and we work constantly to detect and block harmful activity, including removing accounts,” they said. “Our security systems run in the background millions of times per second to help catch threats and remove them before they ever reach you.” (Facebook has given the same verbatim statement to media organizations before.)

Denny does credit Facebook for meeting with him several times since to discuss his situation. Unfortunately, even if the company does an about-face and fully commits itself to hunting down the countless fake accounts on its platform, it’ll likely still be behind the eight ball for quite some time. “Offenders are truly committed to their targeting of victims, so for every fake profile that is removed or blocked, a new one can be created in its place,” said Dr. Cassandra Cross, an expert who has written extensively on the impact these ploys have on romance scam victims. “Anonymity and the transnational nature of offending works in favour of the perpetrators.”

Though the odds are against him, Denny has continued to seek out executives at dating websites and social media providers to highlight the issue. During every discussion, he’s had to answer an uncomfortable question: Why him? Simple: Potential victims “see a guy who’s served his country, has a son, and suddenly lost his wife,” he said. “People want to step up and help that guy out. That’s the great country we live in, the great environment our military lives within. They never suspect those things could be used for evil.”

‘I was so naive. My friends were all telling me it was a hoax’

Sharon Hughes, a 65-year-old retired nurse and divorcee who now devotes her time to painting, is quick with a joke and has a jaunty, chipper laugh and a penchant for off-the-wall statements. “People have told me I’m unstable,” she told me. “I am unstable; I’m an artist!” Although she hasn’t remarried since she and her ex-husband divorced in 2003, she is looking for a life partner. In other words, she’s the ideal target for romance scammers.

In 2015, Sharon was looking on Facebook when a “Ross Newton” popped up in the site’s “people you may know” section. He was a greying, sharply dressed soldier wearing an officer’s uniform, something that appealed to her since she came from a military family. Although she didn’t know “Ross,” the site’s social matchmaking algorithm suggested they connect. Drawn to his good looks, she figured: What the hell? and struck up a conversation. It was a big move for her. “Ross” responded back right away. She was elated.

Within a few months, the two were soon exchanging several messages a day and contemplating starting a life together after he left the Army. Sharon was mesmerized by her boyfriend’s daring stories of combat and dedication to his troops, but she also felt bad for him; he’d suffered a terrible string of luck, including losing some of his closest companions in skirmishes. “There was one time when one of his best friends was injured by a grenade,” she said. “He described in detail how sad it was, sitting next to him as he died in a hospital bed. He got quite creative.”

Courtesy Bryan Denny

“Poor guy, they’ve really used him to inflict an awful lot of pain,” one victim said of Denny, whose photograph once made her fall in love from afar.

Sharon’s desire to help her ailing soldier overshadowed her concerns about sending him money. After three months together, they were engaged (he’d sent her a picture of the ring he’d bought), and she was hunting for their future home. When she’d finally found her dream house, she was blindsided when the homeowner and realtor both told her she was being conned. “I thought they were being ridiculous,” she said. “I told them, ‘He’s on the internet right now. Let’s just send him a message and talk to him!’”

Sharon had a similar experience at the bank when she was encircled by the branch’s manager and two tellers, who told refused to honor the wire transfer she was requesting. “It’s a scam. Don’t do it,” they pleaded. She never had a doubt… until her family friend noticed during Thanksgiving dinner that the man’s uniform in the pictures actually said “Denny” instead of “Newton.”

Ross wasn’t real. By then, she’d sent him over $35,000 in cash and electronics.

Military Scams From Afghanistan

“I was so naive. My friends were all telling me it was a hoax, but I’d never heard of military romance scams,” she said. “I just had Bryan’s image and voice in my mind and I wanted to meet him so badly that I just kept wiring the money.”

In addition to being ripped off, Sharon lost a number of friends who’d grown fed up with her unyielding trust in her distant fiancé. They had begged her to stop, but she had already invested so much of herself into the relationship. There was no going back. Besides, she couldn’t help it — he was a steely-eyed storyteller whose image was unshakeable.

“Bryan’s picture is what really kept me going,” she said. “I loved Bryan’s image, his story, all of it. His identity was just so appealing… real clean-cut, came from a wealthy family, liked nature. I loved the picture of him with his horse.”

Sharon’s testimony highlights a key factor behind the success of Denny’s impersonators: He’s a good-looking dude. He’s got the middle-aged, early gray look of Harrison Ford in Six Days, Seven Nights or Pierce Brosnan in Mamma Mia. When you add in the fact that he’s a soldier and sprinkle in a couple tragedies, it’s easy to see how ladies, under the right circumstances, would fall so hard for ploys bearing his handsome mug.

Another victim, who spoke with Task & Purpose on condition of anonymity, fell for a fake Denny profile under the name “Greg Howes.” Like Sharon, she was a woman in her 60s who met her beau on Facebook. A widow to a Vietnam veteran, she maintained a relationship with her grifter for a full year, during which she sent him $40,000 in cash and $20,000 in Apple products. When asked why she stayed with “Greg” for so long — especially after they spoke on the phone and she noticed his strange accent didn’t match his Jacksonville, Florida, roots — she said she was too sucked in to step back and admit she’d been duped.

“It’s hard to break things off because you’ve gotten very involved and convinced this is something you need,” she said. “It really goes against you when you’re sneaking around doing things you usually wouldn’t. It feels dirty, wrong — but you feel like you need to.”

Although she finally ended things last spring, this victim has yet to tell her family the full story. She likely never will, she admitted — but it’s difficult to hide the heavy debt she incurred sending “Greg” money for medical care and improved electronics for his platoon. Despite being a victim herself, she mostly feels sorry for Denny.

“Poor guy, they’ve really used him to inflict an awful lot of pain,” she said. “With everything they sent over, it’s clear they’ve got more than enough firepower to keep this going for a long, long time.”

Can the law — or anything else — stop social scams?

A couple of months ago, Denny decided to take a weekend trip with his family to a lakeside getaway near his home in Williamsburg, Virginia. Now a defense consultant in Washington and the president of the Second Cavalry Association (the veteran alumni group for the 2nd Cavalry Regiment, which he commanded in Afghanistan), he’s come to cherish these outings, an escape from life’s stresses he was never afforded while deployed overseas. Denny especially loves unplugging from the world, to get off the grid and away from all the victims — if only for a moment.

“The emotional pleas from people begging to speak with you and to rekindle the spark they think you had, it gets to you. It really, really does,” he said. “It’s tough to sit back and watch Americans give away their life savings away to criminals abroad using pictures of me, especially the images with my fallen soldiers.”

Denny may be determined, but he’s not naive. Beyond trying to raise awareness about a drastically underreported criminal scheme, he’s fighting a faceless enemy that the FBI and Army CID say is gaining strength. The people responsible for these crimes are hiding behind keyboards thousands of miles away, protected by a labyrinthine web of fake accounts, stolen identities, and internet back alleys.

With government regulation lagging behind technology’s ever-accelerating advancements, and social media companies incapable of aptly handling these matters independently, there appears to be no expert or authority in the field to rely on. Nonetheless, Denny’s holding out hope that the FOSTA bill signed into law by President Trump in April, which targets websites hosting ads for online sex trafficking, is a sign of more to come. He’s also encouraged by recent conversations he’s had with the Army’s office of public affairs and the staffs of several legislators, including Republican Rep. Devin Nunes and Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein of California — both of whom declined to comment on this story. Denny will also appear in an upcoming episode of CNN’s documentary series, “Inside with Chris Cuomo.”

Unfortunately, he suspects he’s in a lifelong fight. Equipped with an arsenal of photos bearing his suave grin and a laundry list of sob stories, scammers are primed to cash in on his all-American appearance for years to come. Things may be getting easier for them, too, after Facebook announced on May 1st that it’s officially diving into the world of online matchmaking. Their target market? Divorcees and users over 40, Meredith Golden, a New York City-based dating coach, said in a recent MarketWatch story. “There are millions of singles in this demographic who want to meet someone but have reservations about using dating apps,” she said. “If they’ve already been using Facebook and feel comfortable with the format, this will be an easy transition for someone reentering the dating market.”

If Golden’s right, that places Facebook’s core dating niche directly in the crosshairs of romance scammers. And there seems to be no shortage of willing marks.

“I thought the whole thing was funny,” Sharon said after confirming she’d never try online dating again. “Not that I lost money, but that there’s this African guy pretending he’s Bryan and Bryan doesn’t know about it and I’m engaged to Bryan — but in the real world I’m not engaged to anybody. They’re always good-looking, handsome men with good incomes and wholesome devoted lives and it’s all a lie. They’re too good to be true.”